Cultural production is typically ignored by economists and technology writers. At best it is only addressed within the context of various media verticals: film, music, news, and so on. In this post I will begin to correct this strategic oversight by combining a theory of cultural production with some common frameworks for understanding technology and value. This analysis leads to an unavoidable conclusion: the diminishing marginal value of aesthetics.

Why Edgy Aesthetics Have Value

Cultural production moves hearts, minds, and dollars. There are several types of cultural production, but here we are primarily concerned with aesthetic production: the production of images and their value in society.

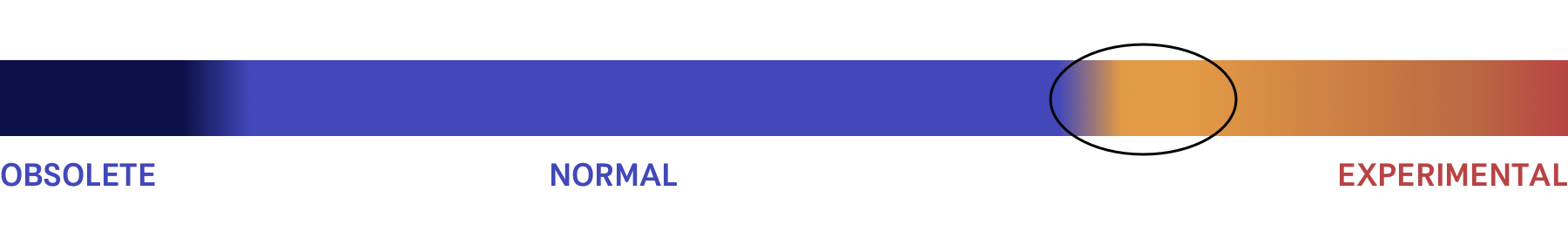

To simplify things dramatically, consider that every aesthetic falls somewhere on the following spectrum. The left side of the spectrum corresponds to wide recognition and acceptance. The right side corresponds to unrecognizability and uncommonness. Altogether, this spectrum constitutes the entire “cultural field” of images.

The large chunk in the middle represents the zone of normalcy, into which fall most aesthetics we encounter daily. On the far left is the zone of aesthetics which are so banal they are generally considered obsolete (such as oversized suits for men). On the far right is the zone of experimental aesthetics. The location where avant-garde artists operate, this zone comprises aesthetics and images that are still hard for most consumers to understand and appreciate.

Between the zone of normalcy and the zone of experimentation, there is a sweet spot. Just outside what is considered normal yet familiar enough to be comprehended, this is where good marketers work. When Weiden Kennedy says they want to capture “lightning in a bottle” this is what they mean: to take something just outside of mainstream culture, aestheticize it, and turn it into marketing for a consumer product. It doesn’t matter how much of a commodity the product is—this works for makeup and sneakers as well as it does for high-performance cars.

Slightly controversial aesthetics cater to the leading edge of consumer culture, a large population willing to spend money in order to maintain its status. As this group consumes, the cultural Overton window shifts to accommodate more and more radical aesthetics, which lose their novel status as they become normalized. The cultural normalcy spectrum flows to the left, and the function of this sort of marketing is to accelerate its natural movement.

What I have described is the essential logic of fashion. Most people associate fashion with the recycling of aesthetics on the far left of the spectrum back into the right, but that is only one function within the general model. It’s important to note that this machinery is not only present in aesthetics and garment design, but applies to innovation in music, natural and social sciences, ideology, and most other areas of culture.

In Marxist literature and cultural theory, it is common to cite the matter of capitalism’s ability to incorporate oppositional elements into itself. Behind that insight, which is usually dressed up in theoretical language, is this regular movement of culture, automated by the existence of cultural producers: artists, designers, marketers, and brand strategists.

Now that we have established that the market values aesthetic edginess, we can complicate this idea by understanding how context and technology affects aesthetic production and consumer reception. Of course, it is not only edgy aesthetics that have value. Aesthetics that simply reinforce demographic associations, for instance, are valuable for selling things to those demographics. But we are interested in aesthetic novelty because we are interested in the limits of aesthetic production.

The Network Topology Constrains Aesthetic Value

The shape of the media environment is an important variable in aesthetic value creation.

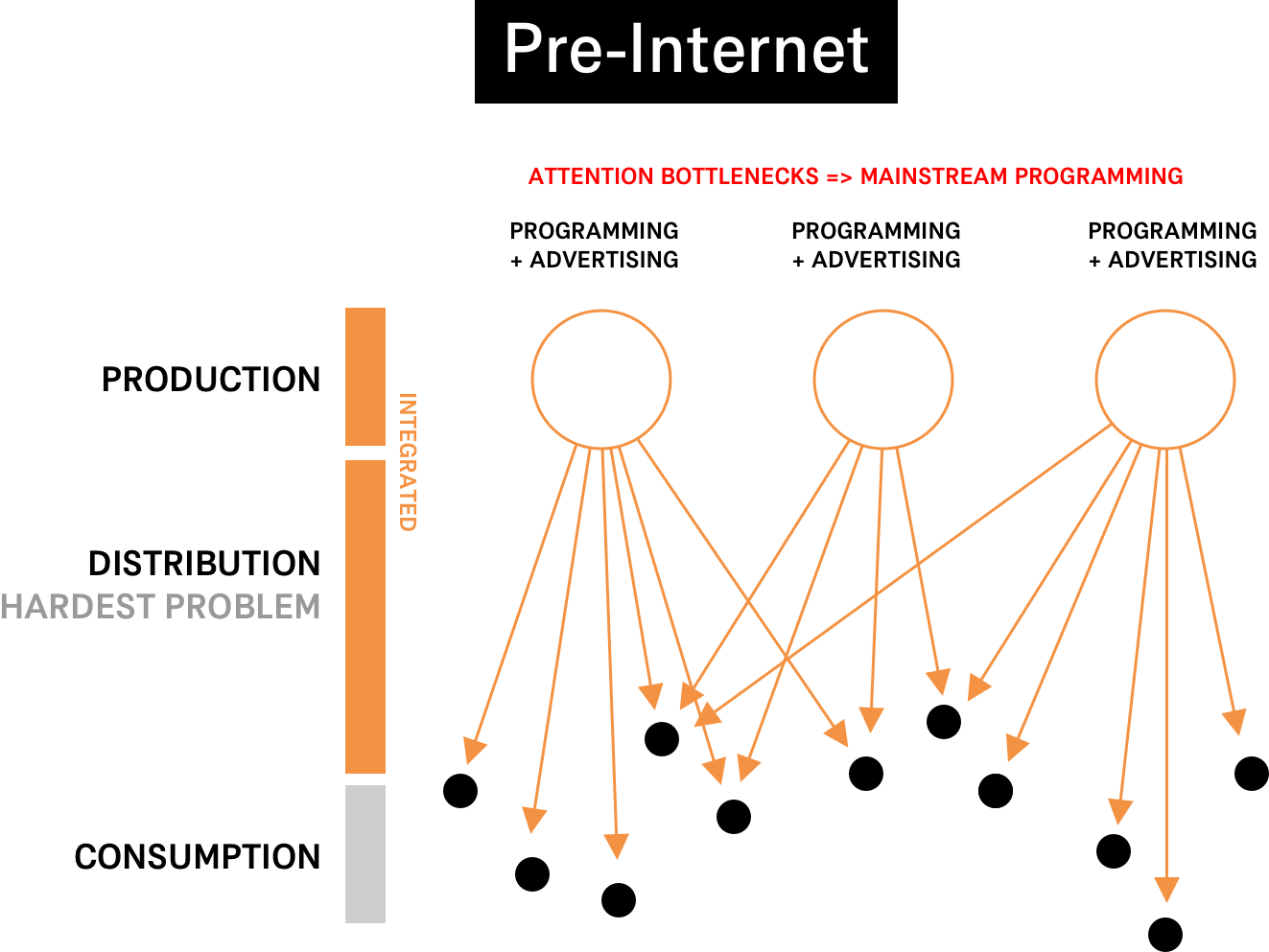

The flow of cultural products in the pre-internet media environment was unidirectional: media channels (network hubs) broadcast toward consumers (terminal nodes in the network), and consumers could only receive visual media, not broadcast it themselves. Some independent broadcasting efforts such as zine culture did exist, but these networks were too limited in scale to be relevant to this discussion. The network was also decentralized, with no single source of media; but it was still concentrated, with perhaps only a few hundred mainstream media channels. This limited number of mainstream channels meant that the majority of available attention was bottlenecked through those hubs. This led to significant advertising revenues, but also posed the challenge of creating diversified programming while maintaining mainstream audience appeal.

It is this largely mainstream programming that provided the backdrop for “edgy” material. When someone like Chris Cunningham rolled an Aphex Twin video on MTV, or when Cartoon Network played Toonami at night, it was broadly perceived edgy to consumers because of two reasons. First, the surrounding programming was firmly within the zone of normalcy, accentuating the difference of aesthetically novel media. Secondly, the low supply of media channels meant that discovering alternative aesthetics was more difficult, heightening the significance (the value) of encountering a unique piece of media.

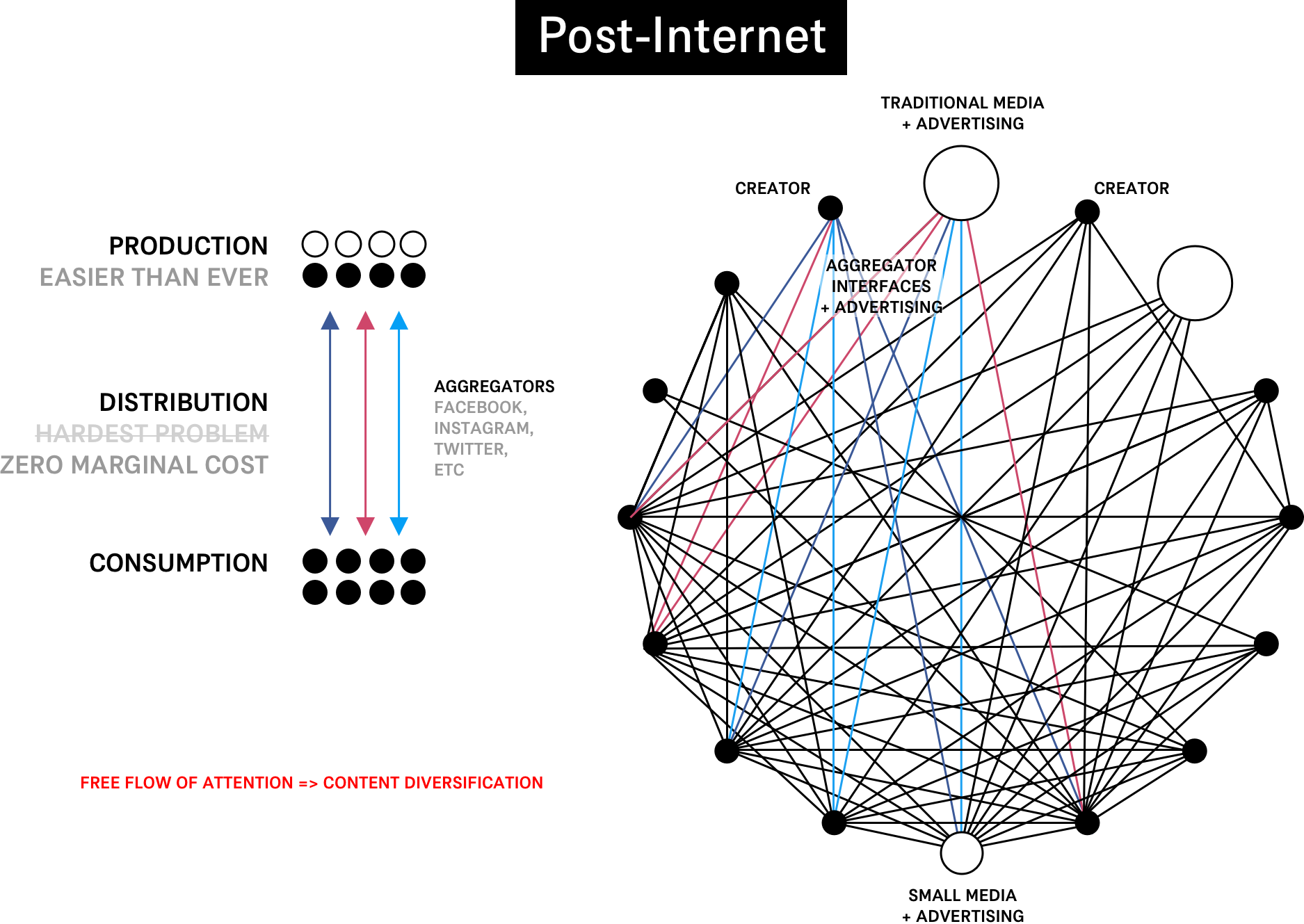

However, today’s media landscape is completely different. The internet has enabled a truly distributed and multidirectional network, in which any node can be a content creator, broadcaster, and consumer. Any two nodes can have a 1:1 relationship; as a whole, the model can be described as many-to-many (M2M). However, despite the possibility of 1:1 relationships between producer-broadcasters and their audience members, those relationships are most often mediated by aggregator platforms like Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and so on.

As predicted by Ben Thompson’s aggregation theory, preexisting media institutions have lost out to these aggregators. But properly understood today, media institutions are not unitary organizations; they are concentrated collections of nodes with presences on aggregator platforms. Preliminary evidence for this understanding is visible in the recruiting practices of some media companies, which exhibit preferences for hiring high-follow-count nodes. Similarly, journalism schools teach social media marketing basics and routinely require students to create Twitter accounts. In short, media companies are subject to the same broadcast dynamics as individual content producers, the main difference being the capital they can deploy to raise production value and promote their content.

This is one example of how technology analysis frameworks and economic models are limited by their customary ignorance of cultural production. In Thompson’s original rendering of aggregation theory, the act of media creation has been reduced to the notion of “user-generated content.” Yet the decline of traditional media companies cannot be fully explained without accounting for the competition between cultural producers and media companies taking place on aggregator platforms.

However, we are not theorizing about the aggregators today; we are theorizing about the consequences of this new network topology on aesthetic production. The effects are threefold:

- Everyone has equal access to every aesthetic. Media is available on demand, as opposed to the time-locked experience offered by traditional media.

- Novel aesthetic strategies are brought to market much faster, thanks to zero marginal cost distribution. (This is not even to mention the falling cost of aesthetic production, driven down by cheap and efficient tooling.)

- Aggregator interfaces impose uniformity of presentation (rectangular images with maximum size restraints), while positioning aesthetic artifacts above and below atomically unrelated items—other aesthetics, images and videos, the news, hot takes, memes, insights, personal updates, and so on. In short, the feed causes aesthetic relativism.

These effects are interrelated, working together in tandem to create various outcomes, some more or less surprising. For instance, universal asynchronous accessibility and low distribution cost means that an aesthetic can never die. Somewhere right now, someone is discovering vaporwave for the first time, and can contribute to its longevity by participating in a lively subreddit. This is why at any given time someone is willing to tell you that the 70s are coming back. The 70s are always coming back to someone. Of course, what is “alive” (that is to say, safely in the zone of normalcy) is not necessarily “on trend” (right-aligned) within the larger context represented by our cultural relevance spectrum.

The main event, however, is a dampening on the overall effectiveness of aesthetic strategies. The combination of ubiquitous exposure and the obliteration of predictable context desensitizes consumers to aesthetic novelty. Just as aesthetics can no longer truly die, it is now difficult to create an aesthetic that will be experienced as truly new.

just practicing lol 🖌️ pic.twitter.com/a0CvF7HuEv

— ⩫⤚𝙻𐍉𐌽𐌴𝙻𐍅𐍃𝙿𐌴𝙲𝙺⤙⩫ (@lonelyspeck) August 25, 2018

Slicing an orange in half and photographing myself sticking my finger in it so that I can get featured on 198 art sites as a "groundbreaking artist" pushing the "boundaries of sexuality" see ya :)

— Sophie (@jil_slander) August 15, 2018

Case Study: The Cultural Producer in an Era of Cheap Production

Creators who make money based on their image production skills are constantly hunting for new references. Their work is paid for and incorporated into the cultural field of images by means of fashion logic described earlier. This creates perverse incentives for everyone to follow the same people, so as not to miss out on what other people are looking at, which in turn creates aesthetic micro trendwaves following the release of anything somewhat novel. A useful case study is the artwork for Jacques Greene’s 2016 album Feel Infinite, designed by Hassan Rahim. After its release, the cover was subsequently exploited and picked over for evermore mainstream audiences for the next 6 months, peaking with the artwork for a Nick Jonas single.

Events like these are becoming more and more common, forcing some fascinating public debates on authorship and creativity amongst graphic designers. Graphic design, the discipline of aesthetic production, is facing a crisis as it reconciles with catastrophic effects of network technology on its profitability. Even prolific designers who produce work with a characteristic original aesthetic are quickly copied. As their work is pillaged and reproduced downstream (leftstream), it becomes increasingly difficult to claim ownership over styles they themselves innovated. These designers are faced with a choice: abandon the allure of an original practice, or double down on the importance of originality and innovate further in order to maintain a competitive margin.

At some point, centering originality in discourse responds to Capitalisms need for product differentiation. Be just 10% different and talk about it a lot, and now you're selling something. Take it too far and it becomes about the enforcement of private property. 18

— Eric Hu (@_EricHu) August 9, 2018

HOW "AUTEURISM" IN GRAPHICDESIGN TURNS OUT AS LIKE THE OPPOSITE OF EMPOWERMENT → ALMOST AS IF IT WAS A TRICK TO GET PEOPLE WORK FOR FREE REINFORCE COMPETITION AND PREVENT SOLIDARITY

— neuroticarsehole (@neuroticarsehol) July 1, 2018

Original typeface by David Rudnick and imitation, via The Fashion Law

Original typeface by David Rudnick and imitation, via The Fashion Law

These challenges apply to design practices like that of David Rudnick. David’s widely influential custom typefaces and compositional style are often pointed to as an aesthetic imitated by everyone from students to established designers. In the face of egregious examples of mimicry, David has remained good-humored but has relentlessly reaffirmed his stake in the techniques he developed and popularized. Publicly he has offered this advice for developing defensible mechanisms against derivative work:

and obviously;

— ཊལབསརངཧ (@David_Rudnick) February 20, 2018

3. Support support support others who take the time & risk to build their own practices and build tools for others. Forget trying to be a hero, be suspicious of anyone who tries to encourage you to be, or wants to be seen as one. Its about all of us, not 1 winner

David’s creative strategies continue to differentiate him from his imitators. But such insistence on original work has been criticized on the grounds that creative “theft” is inevitable. With global visibility and effortless distribution, nobody’s work is safe from being included in a client’s moodboard. In this environment, people cannot be expected to develop a novel aesthetic for every project. Subject to harsh competitive dynamics and incapable of being picky with clients, some designers can only view the struggle to maintain authorship as futile, cynical, and privileged. I followed up with David regarding these criticisms and the present challenges of authorship.

I am in a very lucky position where my practice has a limited level of autonomy and visibility that I am grateful for. Some of that autonomy was gained with the adoption of a strategies that I was actively advised against; by not viewing my typefaces as products for distribution so that I might accumulate capital, I lost income and the cachet of publication, but retained tools that were impossible for outsiders to directly appropriate. I adopted systems of documentation that fingerprint the document-object (work 2) without changing its form-in-the-world (work 1), allowing a separation of tools for distinguishing authorship-in-documentation from the design-object itself.

These are just two of what may be seen as an emergent front of design strategies adapting to this moment of hypervisibility. This goal — at odds with the current model of design education — would be to discover and propagate more methodologies requiring no capital or special equipment or privilege to enact, and which enable designers able to utilize, share and document visual and systemic discoveries without fear that, by doing so, they are immediately sacrificing all autonomy and their tools and voices to entities higher up the visibility hierarchy.

Cheap to produce, free to distribute, yet still impossible to meaningfully automate, aesthetic production is an increasingly precarious vocation. The status associated with aesthetic novelty is eroding, and novelty itself has become difficult to eke out of a system in which everything is visible, accessible, and relativized. The graphic design profession is being strangled in a race to the bottom of the market, and the distributed network topology of the internet is largely responsible; aesthetics has, simply put, been disrupted.

Usually disruptions create new markets, which generate enormous wealth and value. In the case of aesthetics, much of this value has been soaked up by the existing infrastructure providers: PC manufacturers (hardware), Adobe, (software), advertising networks and aggregators (distribution). We do see vast growth in the number of boutique agencies, design studios, and so on. But as I have argued, the forces of technology that have created these markets are simultaneously destroying the monetizable value of the entire cultural category.

The Cultural Production Adoption Lifecycle

The changes brought about by a distributed network and the proliferation of aggregator influences do not stop with people who produce cultural images for a job. In fact, the line has become increasingly blurry.

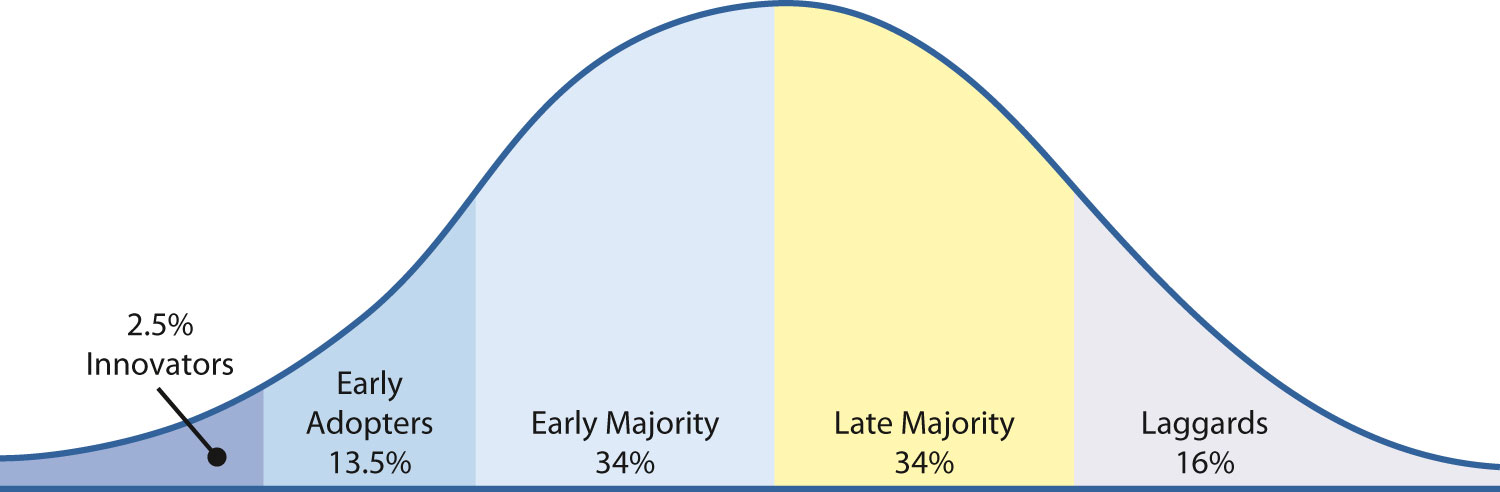

To broaden our view: we must look at image production (and cultural production in general) not just as a specific vocation, but as a novel consumer behavior. The popular Technology Adoption Life Cycle framework proposes that different psychographic consumer segments—early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggard markets—can be penetrated by developing products packaged for each segments. In the case of aesthetic production, these killer apps have not been Photoshop. They have been the aggregator interfaces, which make possible the effortless broadcasting of aesthetic artifacts.

Image via Saylor Academy

Image via Saylor Academy

At the risk of repeating myself, casual broadcasting was not possible before the internet. The separation of broadcasters and consumers in the network meant that client funding or corporate backing was required to pay for the aesthetic production and distribution. Professionally employed designers, photographers, and graphic artists thus had the privilege of being the predominant image producers in society. Instagram, however, has made image producers and broadcasters out of everyone. The multidirectional distributed network of the internet has enabled a once-niche professional activity to become a technology of self-expression. Combined with the technology adoption life cycle, this explains why the loss of Vine was so widely lamented. Its shutdown destroyed a self-expressive behavior with strong network effects in the middle of its adoption by an early majority.

If image and aesthetic production is a fully saturated behavior, we should expect to see that the market for aesthetics is no longer about disruptive, product-driven innovation but about sustaining, process-driven innovation characterized by customer-stealing and market consolidation. In fact, this is exactly what we have, with established graphic designers competing with young guns to sell the aesthetics they originated, and an endless homogeneity of Instagram lifestyle influencers all competing over the same types of aspirational consumer. In the adjacent world of music, a similar competitive dynamic is visible with producers making money selling “type beats.”

Provided we accept this model, we should look for opportunities for true disruption in aesthetics by asking the following questions:

- What are emergent forms of self-expression?

- Where are avant-garde artists (early adopters) making new aesthetic movements happen, and what tools are they using? Turning to the far right side of the cultural normalcy spectrum may be useful.

- What emerging technologies could be used for cultural production in non-obvious ways?

Let’s start with an an example of a technology that has failed to disrupt cultural production: 3D printing. Despite having expressive potential, the barriers to entry (skill and cost) are too high for anyone but tinkerers to adopt it, and it is not supported by network effects.

Crowdfunding, on the other hand, is very interesting. It is strongly self-expressive, supported by M2M network model dynamics, and has been efficiently packaged by companies like Kickstarter and Indiegogo. It’s doubtful, however, that crowdfunding will penetrate the late majority market because crowdfunding products require entrepreneurship, an intrinsically messy activity.

The proliferation of streetwear brands and small middle-market fashion brands is a newer and even better case study. Creating a fashion brand involves all the normal skills of aesthetic production, but does not necessarily require garment production skills, which can be outsourced. Creating a clothing brand solves the context flattening problem posed by aggregator interfaces because a piece of clothing is not merely visual—it can also be worn. Moreover, from the perspective of the cultural producer, a brand is categorically better than a single form of media because of its flexibility—a single brand concept can be expressed through video, images, garments, text, and subsets of all of the above.

"the parents who, in lieu of an iPad, bought their son a £600 birthday pop-up from which to launch his T-shirt brand for two weeks." https://t.co/0E6t5GmJ2n

— Kyle Chayka (@chaykak) July 29, 2018

The crowdfunding and tiny brand revolutions indicate that the business entity can be a means of self-expression and an aesthetic medium of its own. Pop-up shops and one-off capsule collections are effective single-shot versions of this medium, but projects with greater ambitions are emerging as well. LOT2046 and Urbit are vehicles for a set of values for with distinct auteurial aesthetic visions. Both are popularly disparaged as “art projects” because they are equally driven by ideological motivations, but that has not stopped them from being, respectively, a successful subscription business and a robust engineering organization. The business entity is the most important disruptive technology of cultural production to watch. In the United States, recent changes in tax incentives benefiting corporation owners over freelancers provide an infrastructural ground for this hypothesis.

To summarize: why is it worth paying attention to cultural production?

- There are implications for every field involving cultural production: for example, the production and distribution conditions of advertising, political messages, memes, and every possible combination of these image-based media are all subject to M2M network logic.

- The dynamics of cultural production at scale is under-theorized and simply fascinating.

- Financial models for cultural production under contemporary media circumstances are an unsolved problem. The old models are dissolving, and there is widespread dissatisfaction with the aggregator “solution” (in scare quotes because none of the cultural producers are actually making money).

- It’s a way of understanding the media business today—and we are all in the media business now.