The year is 2016 and magic is real. It has materialized, unheralded, in numerous arenas: the growing market for crystals, talismans, and other mysteriati; the cult spellcrafting workshops held surreptitiously in the outskirts of San Francisco and Brooklyn; and most notably, in the popular resurgence of astrology among the young and woke technology intelligentsia. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, you might be too old to be on the bleeding edge of cultural development. Or, more likely, your spiritual senses simply aren’t attuned to feel the growing confluence of power, vapor trails thickening the atmosphere. It is still too early to point to the source of this phenomenon. But here, we will arrange the signs before us and read them to discern the movements of the mystical. What is the domain of astrology today in a time when computation and hard data govern the discourse of knowledge? When consumerism governs the discourse of the self? Does magical thinking deceive us? Or does it offer ideas, and yes, even truths beyond the commonplace?

Astrology must be a popular subject in memeticist circles. As an idea, it has survived at least 4,000 years. Its earliest record suggests that the observation of planet positions was already taken for granted in Sumeria around 2100 BC. Although Egyptian astrology seems to have developed around the same time, the Mesopotamian model became the archetype for all Western astrology. It designated a goddess or god to Venus, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, and the moon and sun, each with its own sphere of influence on the world. Venus was associated with love and horticulture, Mars with war and death, and so on. Later evidence shows that Mesopotamian cultures also identified constellations of other stars, and calculated their positions and movements. To fast-forward a few millennia, this star-cult spread through the Mediterranean and was adapted to Greek and eventually Roman theology, forming the basis for modern astrological practice.

To summarize Mesopotamia-originated astrology: the universe is governed by a divine order, and by the observation of planet and star positions, correlated events on earth too can be understood and even predicted. In other words, ancient astrology is a system of meaning that maps similarities between the celestial and terrestrial. Thanks to Foucault, we know that similitude was the basis of many forms of pre-17th century knowledge. An epistemology based on similarity allowed for a rich tradition of magical thinking to thrive. Viewed from today, astrology is exactly that: a type of magical thinking, one which relies on two similarity patterns. The first is “emulation,” which sees similarities between distant things that seem to answer one another. The second, “analogy,” notices the resemblances of relationships between things. These similitudes are quite familiar to magic, homeopathy, and the like. Take for example the plant thought to heal an illness because its shape resembles that of the afflicted organ. In magical thinking, similitude is not representational, but a transitive property through which an effect is conferred. As noted above, astrology is a cartographic project in the same spirit. It must be emphasized, however, that the ancient astrologer’s readings were thought of not as an allegorical mapping, but as evidence of unambiguous direct correspondence between the earth and the distant heavens, all mediated by the divine order.

A solar eclipse aligning with a poor crop year; a red moon just before a flood. Astrological interpretations always were about their human consequences. However, with the introduction of personal horoscopes in Greece around 200-300 BC, astrology extended into a system of meaning for the self. The constellation and planetary positions under which a person was born could now provide information about that specific person’s life events and disposition. In this crucial historical development, the individual became the prism through which the movements of the heavens were assigned personal and social meaning. Typical birth charts from the Hellenistic period afford information about the innate potential of the subject, from his or her prestige and morality to sexual affiliations. To know oneself was to chart the heavens within the individual spirit. This is Foucault’s emulation, fully realized: man “takes the outward firmament and makes it within himself.”

Personal horoscopes proved to be the stickiest of ideas. Although similitude-based knowledge broke down as the Enlightenment brought a new era of ordered rationality, astrology did not disappear. Instead, it absorbed into monotheistic religions, and easily slid into new formats. In the 20th century, the standalone practice of reading mass-produced personal horoscopes sustained its popularity. Even today, every major local newspaper has its own online astrology section, and internet-based astrologers and mystics such as @poetastrologers, @MysticxLipstick, and Chani Nicholas boast large followings.

But as a determinative system of meaning, astrology has not done so well. For the last century, it has been the subject of both popular and academic criticism. For those who accept the American-led narrative of personal manifest destiny, the suggestion that the planets have a deterministic effect on our lives is threatening and absurd. When asked “what’s your sign?” both ego-driven and hyper-logical types commonly react with derision. On the intellectual front, famed social constructivist Theodor Adorno leveled a scathing psycho-Marxist critique at the mass-produced horoscope, citing its tendency to “transform objective [systemic] problems into subjective and psychological ones.” For Adorno and critics who follow, astrology enables passivity and subordination to the dehumanizing material conditions imposed by capitalism. Finally, the long and storied conflict between the hard sciences and astrology leaves no room for question: astrological predictions of personal events perform no better than pure chance.

Unyielding rationalists like Richard Dawkins denounce “pernicious supernaturalism” as “the enemy of progress”. Accelerationist Silicon Valley demands the integration of technology into just about everything, down to the body itself self. In the face of logic and infinite computation, perhaps the inevitable fate of astrology is to slowly obsolesce into nothingness. Even those who follow the weekly horoscopes seem to treat them with more of a practical attitude than a religious one. Astrology is no longer prescriptive, but representational—“just a tool,” “open to interpretation.” Like past modes of belief, will astrology expire skepticized, demystified, and devalued? What will happen to the map of the self?

welcome to the desert

In the net art and critical theory communities, Society of the Spectacle has seen a sudden renewal of popularity this past year. Published in 1967, the visual metaphor of “the spectacle” detailed therein has only become less bizarre and more disquietingly relatable with time. To Guy Debord and his movement, the spectacle is agglutinated capital, piled up until it solidifies into an image. It has specific forms— advertisement, content, entertainment—and a general one—the permanent and omnipresent realization of our social and economic system. The spectacle is not merely a simulacrum that “covers the entire surface of the world”. Ever-more thickly layered as it mutates and reproduces itself, the spectacle becomes the world we interact with.

This image, unfolded and papered across our lives, forms its own occult diagram, replete with arcane symbols (brand logos) and esoteric prophecy (consumer profiles). Here, the self is understood not by the order of the heavens, but by the ordinance of consumption. Debord portrayed the human effect of the spectacle as a blending of the personal and the commercial. This is a banal observation in 2016, when the purchase and use of commodities as a primary way to construct our identities is utterly normalized. To comprehend its pervasiveness and scale, we must catalog the ways in which meaning in our lives is mapped to the consumption of goods.

An easy-to-spot subsystem is what might be called “techno-spiritualism.” Collective identity, formerly achieved through the worship of gods (the symbol for god is “star” in Mesopotamian cuneiform), is today consummated through the worship of computation. Each spring and fall, ceremonial assemblies come together to prostrate themselves at corporate cathedrals. This custom begins with a rumbling murmur in anticipation of new miracles, which rolls and boils into a convulsive moment, a “fervent exaltation” of a product’s release. The keynote is the new sermon. Finally, the inevitable, purgative act of purchase completes the cycle. Contentment is not derived from actual use of iPads, Dyson inventions, crowdfunded IoT devices fighting for their 30 days of fame. Association with and allegiance to brands becomes an internal self-defining act, while participating in the ritual of consumption itself becomes the goal and the external signifier of personal identity. In this scheme, there is no act worth more respect than joining the clergy. To become an entrepreneur, to dedicate oneself in mind and body to the creation and disruption of new markets, is to be celebrated.

In other ways, the body is already subservient to computation: mass media sustain themselves by fracking attention from our facial orifices. But the true battle for the personal meaning is fought on psychological ground. Even as supposedly progressive groups and self-help gurus champion ideas like “radical self-love,” the beneficiary of self-care seems increasingly removed from people themselves. For the privileged, self-care is undertaken through acts of ever-increasing isolation, marketization, and aestheticization. “Wellness” is the central phraseology of this project. This all-encompassing and self-justifying vernacular enables the sale of everything from kale and SoulCycle to company-sponsored kickboxing classes and stay-cations. The content marketer’s suggestion that eating “a snack with some good protein and lean fats” can “calm your mind from stress” is a perfect example of consumption masquerading as emotional health. Similarly, the tech leader’s evangelization of meditation is an anarcho-capitalist ploy for ultimate productivity disguised as spiritual enlightenment.

Those who prosper within this system of meaning become more and more image-like themselves, called to become the new aesthetics. The mind is made whole by ingesting “clean” non-GMO foods. The conscience is cleared by surrounding oneself with minimalist goods, then dispersing them with periodic Kondo purges. The poor, jobless, and homeless face worse fates. Although global finance capital produced the systems which in many cases caused this plight, its victims are branded “irrational actors.” Institutionalisation and imprisonment is the price for failing to submit to and reflect back the duplicitous story that meaning and contentedness is within one’s own personal control. Ranciere tells us that politics and aesthetics share the ability to delimit the visible and invisible; if the spectacular self is an aesthetic being, then our society’s demarcation of personhood excludes and silences those who literally cannot afford to maintain a self-image.

If this view of our own world is overwhelming, alien, yet nauseating familiar, it has done its work. Here is an entire ontology which forces itself on us, envelops and penetrates us, and coerces us to accept it on its own terms. Within it, the persona is merely subject to the movement of markets. This too is a map of the self, a spectaclist topography by which we navigate personal and inter-personal space. But unlike modern astrology, this system takes itself totally seriously. Meditation, exercise, and an abundance of trendy “superfoods” are frequently offered as actual ways for individuals to adapt themselves in response to the challenges posed by neoliberal capitalism. Here we find that magical thinking has not been retired, but is in full force. The notion that purchasing items with surface-level signifiers like minimalism or “fair-trade” has some correlated virtuous effect in the self is as silly of a proposition as your call getting dropped because Mercury is in retrograde.

Can we say that this world is rational? That computational devices are free of ideology or that materialism is irreligious? By now it should be obvious that we cannot. The surface-level infallibility of these ideas may be comfortable but they are neither pure nor factual. They too are just systems of meaning—social productions whose acceptance as “objective” fact are culturally determined. Retreating to self-determination and scientism allows the twisted logic of the spectacle, no more sensical than that of the mystical, go unobserved and unchallenged. The ancients believed the universe operated according to mysterious divine principle. But neoliberalism is the ultimate cabalistic regime of power. From the trivial to the highest level of abstraction, from how we hold our pencils to how we define personhood, its designs are immaculate, unknowable, unaccountable.

It is from within the interior of this spectacle that magic has begun to emerge. Conceivably, the spirit of the ages, crushed for a century under the pressure of this totalitarian assignment of meaning, has crystallized into a solid form with uncanny properties. All living systems optimize to reduce their entropy by casting it off; magic is simply the concentrated negentropy of late capitalism.

“When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro,” a timely Hunter S. Thompson quote, captures how those with a sensitivity to these strange powers begin to exercise them. It is not surprising that the resurgence of astrology is most prevalent with the last-born generation of millennials. They are old enough to recognize the crumbling, weirdening world, but young enough to resist both ignorant optimism and jaded defeatism; not immune to consumer culture yet inherently distrustful of it. Among this youth, there is a growing sense that something exists beyond the system of meaning handed down to them. Adorno’s critique of the mass-produced horoscope turns back on itself. It is capitalism that demands unquestioning adherence to its strictures. Astrology, by comparison, reads like an act of resistance. Practiced with mindful solemnity, yet also with light-hearted irreverence, embracing astrology is both a contravention of the system and an intervention of the self. Astrology cares nothing for the neoliberal world. Its mechanisms are eccentric, adaptable, spiritual, as simple or as complex as one wants them to be. It opens a space for exploring and defining one’s own meaning. Used in this almost meditative way, mystical ritual is not so misleading and harmful as it is edifying and restorative. We can be our own mapmakers.

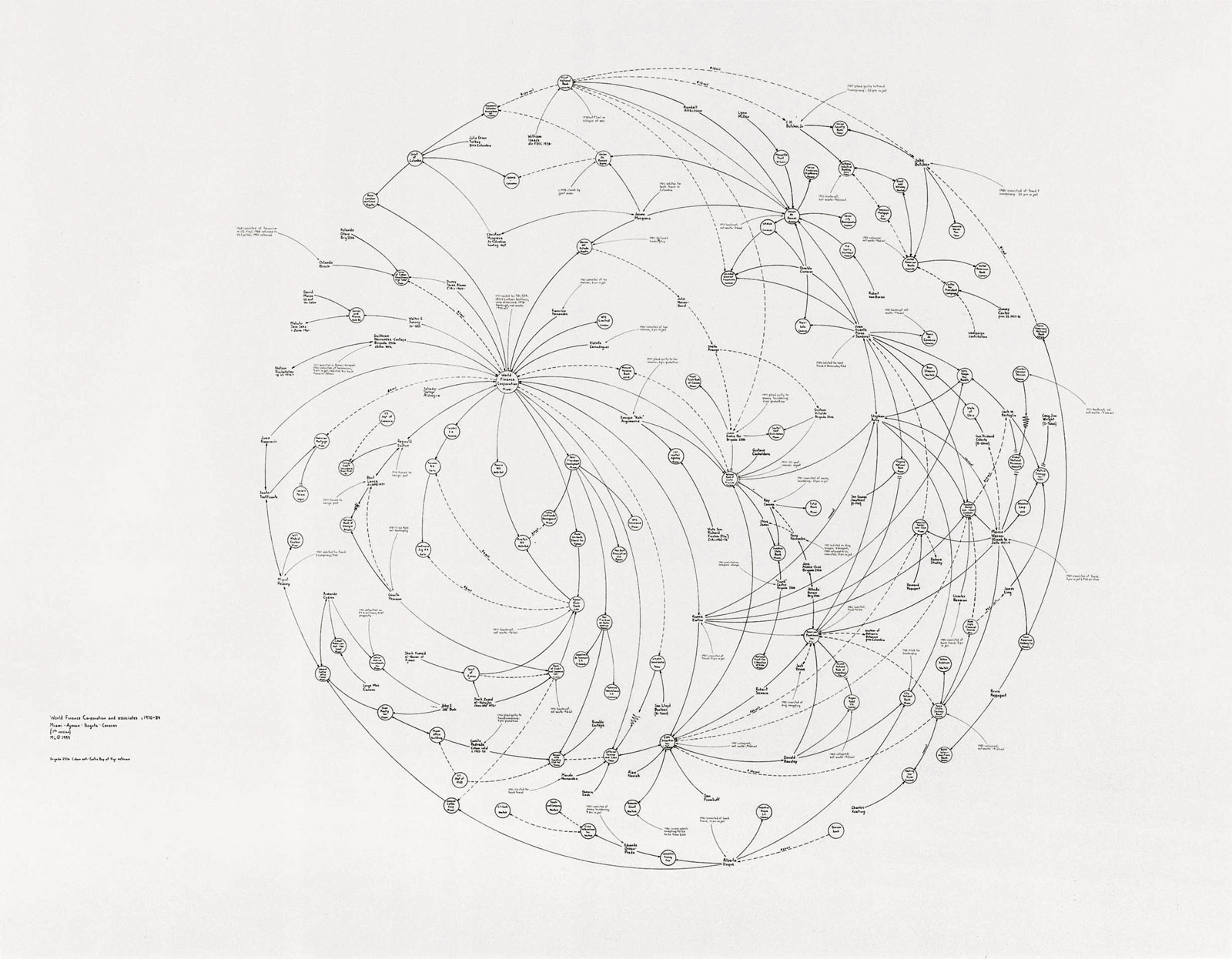

The self is the most personal frontier, but far from the only one. Those who wield magic for themselves soon come to turn their powers on the external world. Magic is first and foremost a speculative exercise that uses media, people, images, words, sensation, and sounds as its palette. Today we may observe a wide range of methods. Some everyday activities, when undertaken by proficient magicians, achieve surprising outcomes. Divinations of cultish trend forecasters reverberate throughout the market. Consumer demand is summoned as brand advisors incantate over intricate arrangements of cryptic signs. Then there are darker and furthermore arcane masteries. Hexes are crafted to agitate competitors, enchantments to ease acquisitions. One even imagines a neoliberal astrology: instead of aspects, houses, nodes, and star paths, there are constellations of financial institutions, politicians, private corporations, and monetary flows. The art of Mark Lombardi is prototype for a new star chart that reads a person’s fate and disposition from their material circumstances and the movements of corporate entities.

In a world where techno-capitalism conspires to dictate all meanings in our lives, astrology and sibling mystic arts must be taken not as fixed universalist systems, but as inquisitive tools to understand and interpret the self, to be played with, tried on and discarded effortlessly. The witch, the cyber mystic or shaman, seeks to transcend the systemic and the personal. “Conjuring supple, playful magic in the shared self/other space,” she blends truth and fiction together, creating new, meaningful realities to dance in.

- Design + Words

- Toby Shorin

- Mood

- STONEDALONE

- Special thanks

- Morgane Santos, Brook Shelley, Catherine Schmidt, Helen Tseng, Wynn Mustin, Abi Laurel, Darren Kong