The uneasy Web 2.0 truce between social networks, legacy media, and brands is falling apart. Once it was held together by ad tech. But advertising spends keep going up, brand content is at peak saturation, and audiences are slowly but surely evacuating the big social media companies. Can the three forces — social media, content, and commerce — find a new way relate to each other?

Here enters the question of community.

As high quality content and effective brand strategy move down the long tail, “community” has become an important concept for every post-Web 2.0 player. Crypto token holders, influencer fanbases, DTC brand customers, creator audiences, and new social networks are all often referred to as communities, and each has a stake in developing community for itself.

A new business type here is the paid community: a direct subscription to join in. Today, most paid communities live on the outskirts of existing social platforms. But as they become normalized, paid communities are becoming a viable business model for smaller-scale social networks aiming to be both profitable and socially sustainable.

This emerging new media thing, the paid community social network, has new rules and new risks, and just as it will require new skillsets to operate, requires a new way of understanding what both business and community mean.

The Emergence of Paid Communities

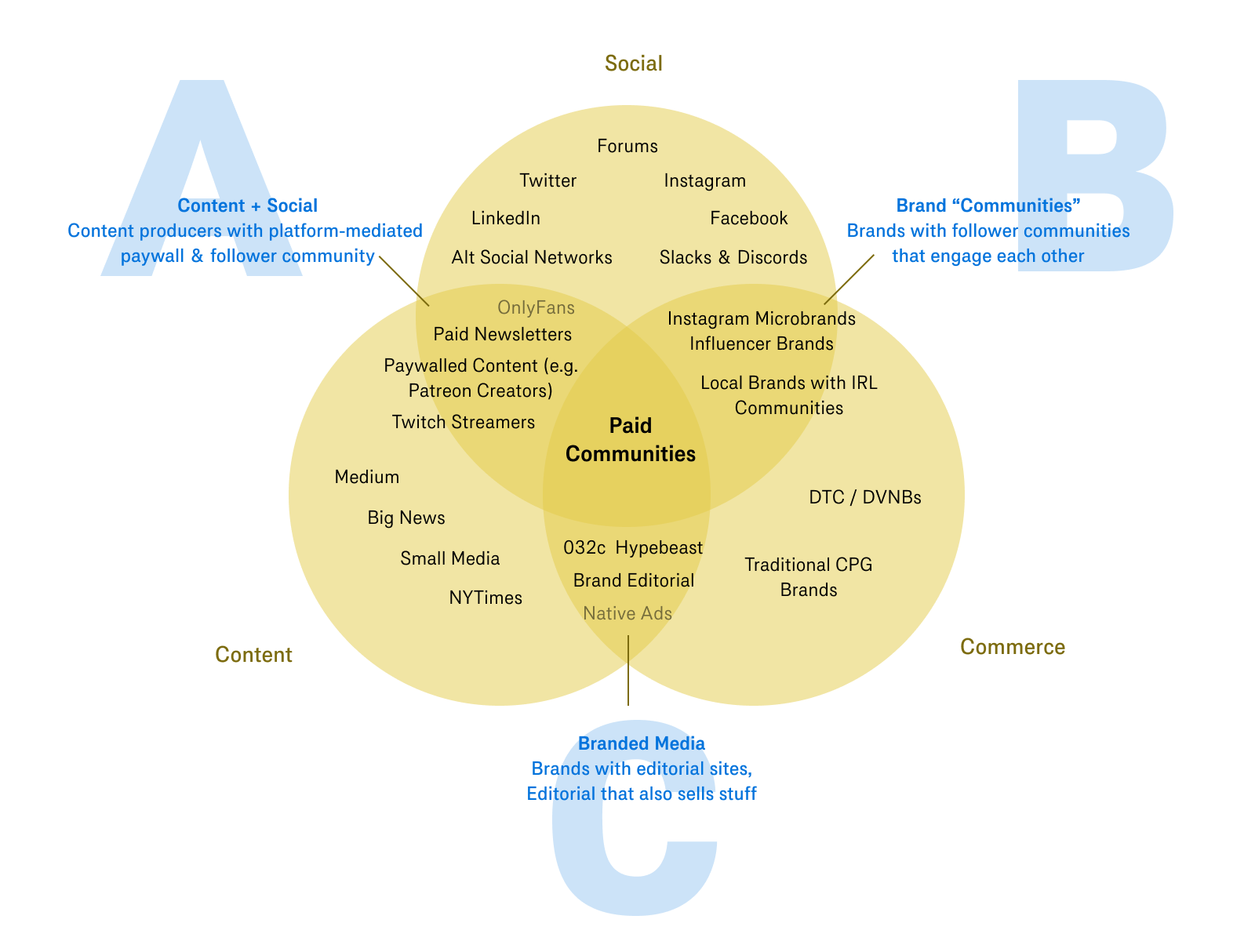

In the last 5 years we’ve seen several interesting innovations as Web 2.0 business models recombined into new mixtures of content, social media, and commerce. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Content and commerce have been merging to create new publishing endeavors that make no distinction between advertising and editorial. These businesses take multiple forms: they include expensive brand-led lifestyle marketing initiatives like the WeTransfer blog and Casper’s Woolly Magazine; “native advertising” efforts like Vox’s Explainer Studio, NYT’s affiliate marketing play with the Wirecutter acquisition; and the extension of lifestyle magazines into product, such as 032c’s streetwear line.

Content and social are also unifying, with Twitch streaming and YouTube being the biggest video players. Meanwhile paid newsletters have taken off in a big way in the last two years. In content + community, an audience connects around a specific content producer through some platform.

Finally, commerce and social are coming together, although to much less a degree than marketing teams who talk up “brand communities” would like you to think. In all but a few cases, “community” here is just the marketing language used to describe a microbrand’s niche Instagram fandom. To me “community” implies users regularly engaging with each other, a criterion which indicates that the “regular crowd” at neighborhood joints or local skate shops are much truer communities than most online brands. Nevertheless, brands are now much better at directly engaging current and future customers through social media. This merger is clearly happening.

Each pairing of verticals has produced some of the most interesting companies and media projects of the last few years. But what’s happening now is that all three are coming together in a new way, fusing to form a completely different type of business: paid communities.

Paid communities are a still-nascent category, but the business model is familiar: free content with a subscription paywall for more (the standard model of content + social). Paid communities develop this formula further: they take the subject matter of a content producer or brand lifestyle, and pair it with a paywalled digital social space for ongoing user interaction. Here the community is not a passive audience, but one that generates its own discussion, and for users comprises much of the value in and of itself. This community often comes to re-shape the brand or content development process.

Here are a few examples of burgeoning paid communities you might have already heard of:

- Stratechery: paid content + members-only forum, for investors and tech strategists.

- Venkatesh Rao’s Art of Gig / Yak Collective: paid content + a Discord channel, for indie consultants.

- New Models: content aggregator + commissioned content + paid Discord channel (conducted through Patreon), for artists and cultural producers.

- It’s also worth mentioning that Substack is currently layering on commenting + social features for paid newsletters, so many successful Substacks qualify.

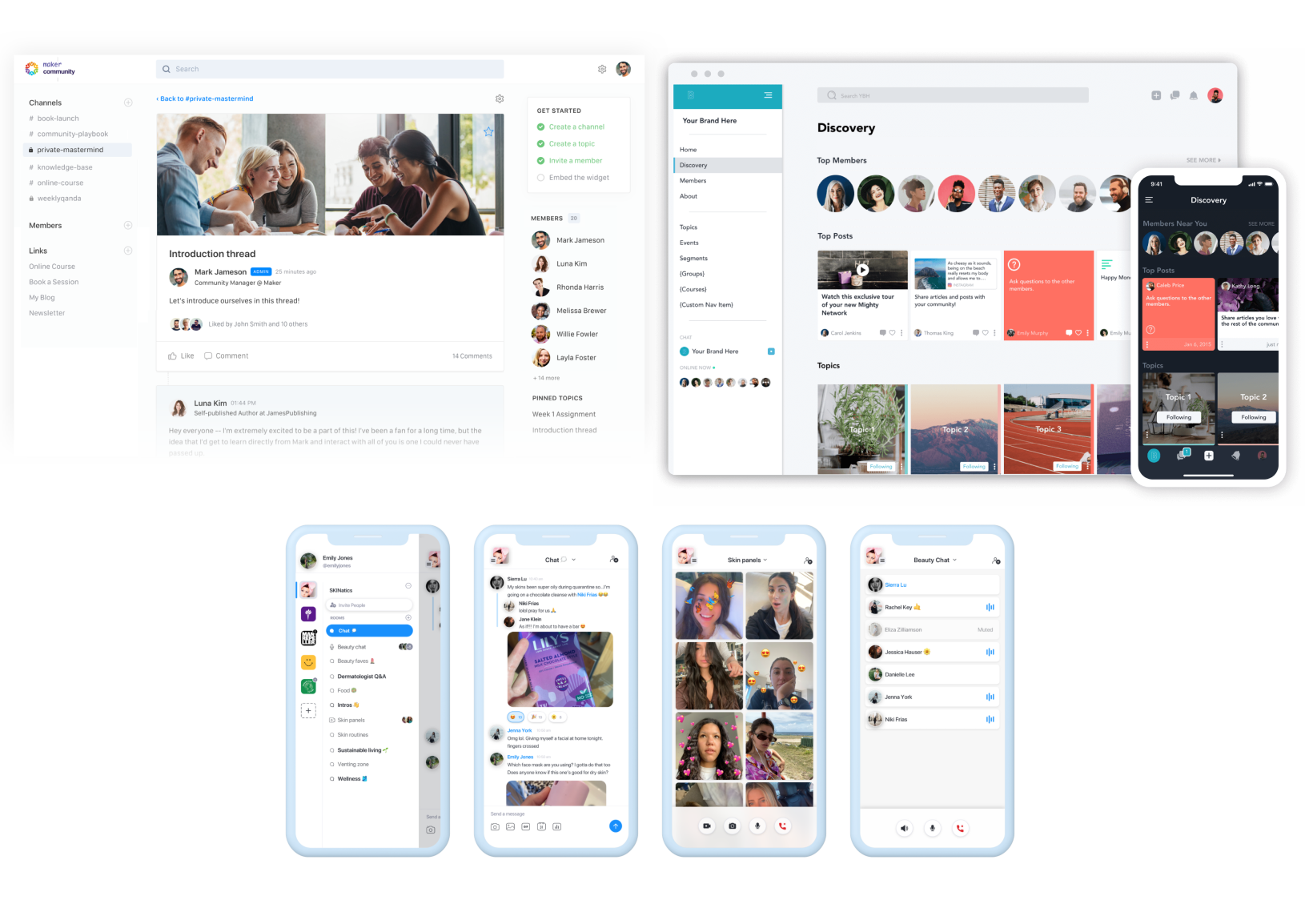

These new paid communities largely live on invite-only Telegrams, Slacks, Discords, and Facebook groups, raising the question: could there be applications more suitable to these networks? Indeed, the growing popularity of paid communities has been noticed by a bunch of new venture-funded companies such as such as Genevachat, Mighty Networks, and Circle, all of which want to become “the platform for communities.”

Ironically, these “community platforms” are themselves largely clones of Slack and Discord. They have been designed to fit what already exists on the market — to generically scale to support every possible group — in order to drive the user numbers that can support venture-scale returns. With heavy competition and no differentiation, how could any one of these new platforms become successful? This paradox reveals the limits of venture capital logic. An alternative market analysis is needed to understand this emerging space.

Patreon is a good example of why generic community platforms are not the future. You could certainly say that Patreon is already at the center of content, social, and commerce. But of course, Patreon has for years been getting unbundled into A, B, and C type businesses. The reason for Patreon’s erosion is that its product design is totally unsuitable for all three use cases: it’s a bad brand platform, a bad content platform, and a bad social platform. Patreon is a classic case of what Venkatesh Rao calls “Too Big to Nail,” and businesses that try to follow in its stead will face similar challenges.

Don’t buy into the VC hype on this one. There will not be one tool to serve new internet-first communities.

Paid Communities Are a New Business Model for Bespoke Social Media

Meanwhile, dozens of alternative social networks have sprouted up in the last couple years. With the maturation of Javascript-based web development and plenty of front-end talent, it’s become easy to build complex web applications with tiny teams. futureland.tv, Dialup, Special Fish, and alternative dating app Bighead are among these new experiments. These alternative social networks are interesting in part because they prove that dissatisfaction with mainstream web has motivated significant movement to alternatives. But they are also interesting because of their unique user communities.

New social networks have typically struggled to monetize due to their small audience sizes, as they are unable to achieve the scale to make meaningful revenue from advertising. Paid communities, however, supply an engaged and paying audience, providing an alternative route to sustainability for independent social networks. At the same time, social networks solve some of the deficiencies of paid content and brand communities. This is worth understanding well.

Businesses want to be active participants in their customers’ social landscape, because brand values are the last battleground for differentiation. This is the very justification for community marketing, and the driving force behind the evolution of brand social media accounts from joke memes to increasingly woke and personal human voices. Offering a dedicated social space is a further extension of social participation. By providing a social space, brands can try to deepen their connection with users and have a place for content they produce to be discussed.

Similarly, the topic-specific functionality entertainers build into their streams can be seen as prototypes for rich social spaces. In journalistic media, content providers with growing audiences also need tools to manage their audience and moderate discussion. Slack’s 10,000 message limit for free accounts is a major obstruction to doing knowledge work in these spaces, and Discord’s free tier has lamentably small file upload size limits.

At this point, you may wonder: “why don’t users just want one place to manage all their communities?” Today’s existing tools will continue to be sufficient for some communities, and Discord and Slack’s robust bot APIs are capable of solving some community needs. But fundamentally, they are still based on chat, and chat simply isn’t the right core user experience for many other communities. Unique functionality and bespoke interfaces provide distinct advantages that off-the-shelf tooling can never achieve.

In order to understand how diverse and specialized these paid community / social networks can be, a few case studies, drawing from different scales, will be helpful.

Replit

Replit is a community of young programmers, supported by a forum, a real-time collaborative IDE, and a library of openly forkable code projects. The deep integration between Replit’s social space and its programmer tooling enable efficient knowledge workflows and sharing of user-generated content. At the same time, it facilitates the growth of a highly collaborative culture specific to this set of tools. Replit has gone the venture capital route, monetizes through a premium offering including paid cloud storage and unlimited private projects.

Are.na

Are.na, founded in 2012, can claim to be one of the most successful indie social networks. (Disclosure: I am a shareholder through its Republic crowdfund.) Originally bootstrapped by a small community of NYC-based artists, it has grown to over 12,000 monthly active users, largely designers, artists, researchers, and educators. For these users the restrained interface, absence of an algorithmic feed, and community of intellectuals and cultural producers have made it a popular tool. As of May 2020, Are.na took in a respectable $20,000 monthly recurring revenue for its premium feature set (group features and unlimited private blocks), and posted strong retention numbers. Though some have described Are.na as “nerdy Pinterest,” it is this same niche focus, “white cube” aesthetic, and longstanding community channels such as Freak Hacks and Images With Captions On Wikipedia that make it a choice place for designers and artists to collaborate.

Bloomberg

Bloomberg is one of the world’s largest and most valuable companies. It provides financial data and analytics tools through its ubiquitous Bloomberg Terminal, which costs $35,000 per year to license. What most people don’t know is that the Bloomberg Terminal contains hundreds of microapplications, including Bloomberg-exclusive social tools. Byrne Hobart puts it thusly:

The key point to understand about Bloomberg is that it’s both a software product and a social network. The software product determined who would join the network, but the network is what keeps users there. It’s like a multiplayer video game, or Harvard: Sure, the quests and campus are useful, but people keep showing up because of the friends they’ve made or the connections they intend to make.

Among other social apps, Bloomberg Terminal features a Bloomberg Hacker News clone, a Bloomberg Craigslist clone, Bloomberg instant messaging, and Bloomberg-restricted email. From this perspective it is possible to view Bloomberg as a company that offers a full-stack set of social environments, news, and tooling for a distinct community with specific needs: financial workers. While Bloomberg shows what is possible when the community in question already works with large amounts of capital, its lessons are applicable to niche content providers.

..

Bloomberg is an example of the classic Web 2.0 business maxim “come for the tool, stay for the network.” But the inverse trajectory, from which this essay takes its name, is now equally viable: “come for the network, pay for the tool.” Just as built-in social networks are a moat for information products, customized tooling is a moat for social networks.1

This entrenchment effect provides a realistic business case for bespoke social networks. Running a bespoke social network means you’re basically in the same business as Slack, but for a focused community and with tailored features. This is a great business to be in for the same reasons Slack is: low customer acquisition costs and long lifetime value. The more tools, content, and social space are tied together, the more they take on the qualities of being infrastructure for one’s life.

By now you might be starting to think about businesses and communities could benefit from paid social networks. I posed this same question to my colleagues at Other Internet and we devised some interesting answers:

- Small media organizations

Aggregators like New Models and popular paid newsletters or podcasts which are increasingly cultivating community discussion may soon arrive at a point where their subscribers themselves generate enough interesting content to become part of the publishing workflow. What mixed media discussion + writing + recording social space would support this? - Custom tooling for streamer communities

Relatedly, streamers on Twitch could benefit from a tighter integration of broadcasting tools, chat, and rewards, currently handled through awkward OBS ↔ Twitch ↔ Plugin workflows. - Small-scale political community organizing / mutual aid

Instead of a chat feed, perhaps here would be periodic goals and interventions that people work towards — like a action-focused Nextdoors for specific areas or missions. - Chat groups for gaming and fantasy sports

A community space designed for Dungeons & Dragons players that includes character creation interfaces, dice tools, and ways of carrying out campaigns is going to be dramatically richer and stickier than a Discord. For fantasy sports crews, one can imagine a number of betting, picking, revealing, and game mode interfaces, particular to the idiosyncrasies of different communities. - Hobbyist communities currently served by traditional retailers

Brand networks that assemble niche social communities around an activity that the brand uniquely facilitates, e.g. the Bass Pro Shops community where you chat but also have a convenient interface for building out and displaying your jigging setup. I’m surprised this doesn’t exist for gun enthusiasts yet. - Education and practitioner networks

We’re seeing a lot of new venture funded education communities, but here once more is a reason to be more excited about bottom-up community-driven businesses. What happens when groups of independent teachers or consultants who are already chatting have shared interfaces to formalize, quote, and invoice? In the past, guilds have provided excellent education opportunities, and they can again. - Food influencer communities

In which you only get access to the recipes and discussion if you subscribe. It’s kind of surprising this one doesn’t exist yet, considering what a poor substitute Instagram is. - Entertainment and fandoms

The evolution of fan forums probably looks more like bespoke interfaces designed by the companies which actually create the characters. JK Rowling’s “Pottermore” is an early example of what this looks like; later communities will likely be more video-focused, and will borrow from the ARG toolkit to involve users in ongoing plotlines or reality TV style dynamics. - Programmer communities

Replit leans young and isn’t tailored to any specific language; there will be more communities and tooling suited to particular types of language, and perhaps around specific open source projects. - Communities that govern things

The crypto community has spawned several interesting use cases for bespoke, paid social networks. Some crypto protocols, like Compound and Maker, allow token holders vote on changes to a token economy. Other crypto communities, like Moloch and its siblings, have users buy in with their own funds and then vote how they should be collectively allocated. These tools are still rudimentary, but here we see a tight integration of tooling and discussion that is applicable in other governance contexts (e.g. municipal governance participation, voting on actions an influencer takes, etc.).

(Thanks especially to Bryan Lehrer for his contributions to this list.)

Community, Coordination, Conclusion

So far I’ve put forward an argument that paid social networks are a feasible and practical business. But as indicated above, there will be many different types of paid social network, and some will be more sustainable than others. In the coming years I expect this business model to feature prominently in debates about business practices. Most business writing lacks a meaningful engagement with the question of whether the strategies, tactics, and trends on offer are good, in a larger and longer term sense. It is negligent not to address these questions. In this final section I will speak to the issues raised by this merger of content, social, and commerce, and how they can be thought about.

What does “community” mean? Facebook calls its billions of users a community, and multinational brands use this word to refer to their customers. Are these communities in any meaningful sense? What about the “brand communities” I mentioned earlier, do these qualify? And can a community that is paid truly be called a community at all? As paid communities become more prominent, I expect to see these questions asked more frequently and urgently. Marketers, venture capitalists, and business writers will answer from one perspective, offering up ways to monetize large swaths of people. Journalists and critics will reply with a different perspective, decrying organizations for extracting value from relationships. And I imagine we will hear the voice of communities themselves, defending just who they are from both sides.

Different users of the “community” word have different motivations, and these motivations will be the origin of conflict — conflict not only about the word’s meaning, but about how this type of business should be operated. But these debates, no matter how uncomfortable, should be had. Because in a very real way, the financial and social sustainability of paid communities will depend on the degree to which the communities are recognized not as a monetizable resource but as a body of people with social needs, emotional lives, and practical concerns of livelihood.

Companies, influencers, and content creators frequently clash with their customers and audiences. Both companies and audiences make demands and take actions the other party deems unacceptable. Paid communities and social networks are unlikely to be an exception. But they also present opportunities for improving alignment and making this relationship less adversarial.

Success here will come down to implementation details. The incentive structure, funding sources, size, goals, moderation approach, and community management philosophy of these networks will determine their long term viability as both businesses and communities. Whether coming at it from the angle of social media, brand, or content creator, building and managing a community is its own skillset. Organizations which try to bolt on community or social networks to their existing business model without building the capacity to understand and engage the people who make it up are likely to fail.

One of Web 2.0’s most crucial lessons is that extractive business models cannot be masked by marketing for very long. This is doubly true when the community itself is part of what people are paying for. Users will quickly turn on network operators if they sense hypocrisy or are given no voice in the development of the service. I am least optimistic about the prospects of paid social networks run by large corporations, brands, and IP holders. For instance, if a major entertainment company operates a fandom social network, the content and features it develops are likely to support the revenue goals of the company over the community’s social well-being.2 Earlier in this piece, I voiced a similar skepticism of so-called “brand communities,” in which the members are often quite transparently viewed as free marketing resources. I expect many projects along these lines to end with multiple rounds of community frustration, exit, and further monetization.

The inevitable failures, however, should not discredit the entire project of bespoke social networks designed around specific community needs. Prospective entrepreneurs, operators, content creators, and designers are the “social engineers” of these spaces, and here is found the transformative potential of the model. Here, design, development, and content creation are no longer merely tools for generating revenue; they are also tools of community organizing. Here, design and engineering take on the valence of care, and the emotional involvement of being a contributor, moderator, and member. Where does “design” end and “moderation” begin? Because the mainstream social networks have been designed by a tiny number of people, we have been prevented from experimenting and creating new knowledge about what sustainable community management online looks like. Start erasing the line between operators, customers, and community members and squint; you begin make out the shape of a group of people who can build for themselves and determine their own path of development.

These days I find myself away from broadcast tools and more in the insular channels of my friend groups. What I want from technology is to share life with my friends; to be given the opportunity, and the power, to share that life, and all it includes… showing them care, or sharing the bits of knowledge that seem important to us as a group.

To reinforce the fulfilment of collective potential in whatever direction our groups take off in. Some of my friends watch stuff together; some of my friends remark on goings-on; some of my friends research together; all communicate entirely differently. Not all of them belong on "IRC, but for gamers," or "IRC, but for highly productive and extremely important teams." And yet, that's where we are.

I take my own definition of the word “community” from educational theorists Etienne and Beverly Wenger: “communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do, and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.” I like this definition because it is so broad while capturing a really specific truth about groups. It applies as much to my funny little squad of researchers and designers as it does to “weird twitter” and to group psychology participants and to token economy managers, and to families. As disparate as these things are, they share one thing: even when we don’t know who “us” is yet, we’re all learning how to become who we are. Identity is always about groups, and group formation is always about identity formation, and both are processes of learning.

As more and more identity formation happens online, it is inevitable that most of it happens in private spaces. As we spend more and more time living in these spaces, it’s inevitable that their intentional shaping should become more important to us. As more and more internet-first communities choose to build the means for themselves to live, it is inevitable that both “community” and “business” will take on new meanings. We are transitioning from an era of centralized management of human development and financial capital into an era where both identity formation and resource allocation happens in decentralized, loosely-coordinated, and emergent ways. I think we will gain the most learnings about the future of business and identity not from top-down corporate models of community management, but from friends, squads, and content creators starting groups and supporting the legitimate participation of community members in their ongoing development, finance, and governance.

Thanks to the Blogger Peer Review for ideation, editing, and review, namely John Palmer, Bryan Lehrer, Kara Kittel, Matilde Park, Edouard Urcades, Arthur Roing Baer, David Cole, Laurel Schwulst, and Tom Critchlow.

Responses

Aaron Z. Lewis has written a public response to this essay over on his own blog. Click through to read the full thing!

The digital community organizing that you describe in your post seems like a more sober-minded rendition of the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace (which John Perry Barlow apparently wrote while he was drunk). The internet is clearly shifting the balance of power, but it hasn’t led to the moneyless disembodied utopia he envisioned. Barlow said, “Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here … Ours is a world that is both everywhere and nowhere, but it is not where bodies live.” This idealistic dream brings to mind Marc Andreessen’s recent confession that the “original sin” of the internet was not building a payments layer into the browser. The paid communities you investigate seem like an attempt to remedy that sin and ground cyberspace in the material/economic systems that support our livelihoods.

I want to share some loosely connected reflections about online communities and how they might interact with legacy governance structures in the future. Topics on the docket: distributed universities, hype houses, Kanye’s charter city, the political “grain” of online platforms, Silicon Valley’s desire to “disrupt” the nation-state, and digital localism.

Twitter acquaintance Romain from French brand strategy agency hellofdp wrote a public response on his newsletter.

I think the notion of “bottom-up community-driven businesses” is really important here. The paid community concept is a reconfiguration of digital communities caused by the failure of big social networks to ensure deep vertical communities to thrive. It provides mainstream tools to niche communities. Maybe niche communities need niche products? One hypothesis could be that “bottom-up community-driven businesses” emerge when one community is mature enough to have all it takes to self-organise itself and separate from big platforms. Then the question of sustainability and incentives mentioned in the last part seem of the highest importance. A different kind of chicken and egg problem than what big platforms face.

Endnotes

-

Eugene Wei comes to a similar conclusion in his Status as a Service. ↩

-

Thanks to Kara Kittel for this important point. ↩