Has it occurred to you that nobody talks about sellouts anymore?

Recently on my commute I passed someone wearing an Obey shirt. I was reminded of friends and internet commenters on forums I once frequented. They used to gripe about Shepard Fairey leveraging his success as a street artist to create the Obey skate clothing line. Their complaints always came down to “authenticity,” something Fairey ostensibly surrendered when he turned his classic Andre the Giant image into a saleable commodity.

But I haven’t heard about anyone selling out in a long while. Sometime between 2008 and 2018, capitalizing on your success as an artist to build a skate brand went from being reprehensible to being the thing that everyone is doing. I’ve heard people credit this phenomenon to Kanye and Yeezy Supply. Stories are memetically powerful and Kanye’s celebrity martyrdom to create his fashion brand is a story of mythological proportion. Did Yeezus die so we all could sell dad hats and zines? His skate-inspired tour merch popups for Yeezus and The Life of Pablo have inspired copycats, but this goes beyond streetwear, beyond fashion. Right now merely having a self-branded commercial presence is itself seen as a meritable achievement.

Shepard Fairey’s commercialization was deemed problematic, yet the same thing today would today be considered utterly normal. It seems reasonable to suggest that the cultural obsession with authenticity has evaporated entirely. All forms of “personal branding” are just one facet of an ethical shift of such enormous proportions that it encompasses nearly every major cultural development of the last 20 years, and authenticity is at the heart of it. During the first two decades of the 21st century we saw the rise of a caste of self-appointed authenticity custodians we called “hipsters.” We saw the development of an visual aesthetic and a language of authenticity that dominated millennial consumer culture. And in the dwindling twilight of authenticity culture we saw the rise of a new ethical paradigm.

Authenticity vs Commodity

What is authenticity? Of course there’s no such thing, but that hasn’t stopped anyone from believing in it. Nearly 80 years of anthropology research on authenticity-seeking behavior reveal authenticity to be one of the stickiest modern superstitions. The bulk of the early research is about tourism, an activity frequently motivated by a search for this mythical quality.

One widely cited study shows that tourists who are concerned with authenticity reject souvenirs that are made for sale to Western consumers. For these tourists, authentic objects must not be “manufactured specifically for the market.” They have to have an “original” use value and purpose as intended by a native craftsperson (Cohen, 1988). This gives us a pretty good idea of what authenticity means, or at least what it meant: something special, something unique, something priceless, not a commodity, not touched by money.

In the 20th century this concept of authenticity was apparently so self-evident that the anthropologists themselves often failed to see outside of it. Researchers like Dean McCannel praised the value of “original” experiences, such as participating in a traditional dance, and complained unsubtly about “staged authenticity,” the same experience produced for the benefit of a paying Western tourist (McCannel 1993). Igor Kopytoff describes a similar attitude amongst anthropologists returning from field studies:

African art picked up randomly in the course of fieldwork was placed entirely in a closed sphere with a sacred cast. The objects collected were greatly singularized; they were held to have for their collector a personal sentimental value, or a purely aesthetic one, or a scientific one, the last supported by the collector’s supposed knowledge of the object’s cultural context. It was not considered entirely proper to acquire an art object from African market traders, or worse, from European traders in Africa, or worse still, from dealers in Europe or America. Such an object, acquired at second hand, had little scientific value, and it was vaguely contaminated by having circulated in a monetized commodity-sphere—a contamination that was not entirely removed by keeping it thereafter in the same category as the objects “legitimately” [read: authentically] acquired in the field.

These samples from academic literature reveal that authenticity has a rather anti-capitalist flavor to it. (They also reveal that authenticity tourism is distastefully infantilizing to non-Western cultures.) Authenticity is seen as mutually exclusive with commoditization, the process by which things become valued primarily for their exchange value as goods and services in a market. The images above are from Rand African Art, the website of a collector and salesperson. Tellingly, the top piece of text on his website is “Items from my collection are generally not for sale.”

I must emphasize that this is simply how authenticity has routinely been constructed. I am in no way endorsing this definition as truth. Over at Ribbonfarm Sarah Perry has artfully shown that supposedly authentic objects are often used as money in their native culture. As we’ll see later, believing in authenticity can have harmful side effects and may be damaging to your health. But first a little history.

Authenticity and the Hipster Identity

Step back with me 10 years to 2008. I was in high school. Obama had just been elected. Web 2.0 platform centralization had not yet occurred. The indie web was still strong and so was indie music. This was the era of Blogger.com, Livejournal, and Mediafire. It was incredibly easy to discover and download new music on the internet.

The hipster was the archetypal figure of this music blog culture. If you asked a hipster what he was listening to, he was likely to respond “you probably haven’t heard of them.” This exchange was so common at the heights of the mid-‘oughts music blogging frenzy that it quickly became both a hipster shibboleth and a way to satirize the entire movement.

The “sellout” critique was another hipster rhetorical favorite. When a band joined a major label, played on too many mainstages, or made their music more accessible to a mainstream audience, the hipster was quick to denounce them as sellouts and move on to something still obscure. Furthermore the hipster would probably claim he had listened to the band when it only had a shitty demo tape and 100 MySpace followers—“before they were cool.” For the hipster, being released on an independent label was privileged over signing to a major label. Better yet was being self-released and only discoverable through blogs. Best was having zero promotion and being downright unknown—something only you had heard of.

The parallel between hipster consumption of music and the African art fetish of 20th century anthropologists is striking. If authenticity is only a characteristic of “singularized” non-commodity items then hipsters are easily understood as an authenticity-seeking culture. This reframing makes sense of many classic hipster behaviors, such as thrifting. Naturally, a beat-up graphic t-shirt found at Goodwill is more authentic than any name-brand good.

The aggressive cynicism of hipster responses to popularity reveal how deeply the hipster identity was situated within the authenticity paradigm. Hipsters clearly experienced a loss of value whenever something they liked entered the realm of mainstream pop culture. Their authenticity craving was not limited to music but extended to fashion, film, accessories, and other media. As Kelsey Henke notes, “the common thread between contemporary goods purchased by the hipster is that they are difficult to appreciate” (Henke, 2013). Unlistenable low-fi bands, Pabst Blue Ribbon, ugly headbands, and creepy facial hair all fit the bill. “The appeal in this circumstance is that since few people will find value in this item, it retains potency as an extension of the individual.” Here we see there’s a personal dimension to authenticity as well; the hipster consciously avoids similarity to others in order to feel like her most authentic self.

While this ethical framework called “authenticity” informed hipster activity, it would be wrong to assume that it is deterministically and directly responsible for their behavior. On the contrary, it is the claims and behaviors of hipsters identified above that provide evidence for the existence of the authenticity paradigm as such in mid-‘oughts youth culture. Values are intangible but they are always practiced actively and often self-consciously in the messy real world. For instance, the hipster’s moral aversion to commodities and the processes of cultural capitalism is observable in their selective consumption practices.

Of course, those of you who lived through this era know that hipsters were patently conspicuous consumers of commodity goods. What about all the Keds, Parliaments, and Three Wolf Moon shirts?

Mainstream culture and commodity goods present a problem for people who believe in authenticity. But according to R. Jay Magill hipsters solved this by “reactionary distancing—aestheticizing, ironizing.” Viewing the junk products of pop culture “ironically or anthropologically….from internally afar” allowed hipsters to see them as something not part of themselves (Magill, 2007). Hipsters also perform their distaste for “the clichés and spectacles of pop culture” through acts of public cynicism about mainstream goods (Henke). Ironic consumption of commodities is one way hipsters discriminated between the authentic and inauthentic.

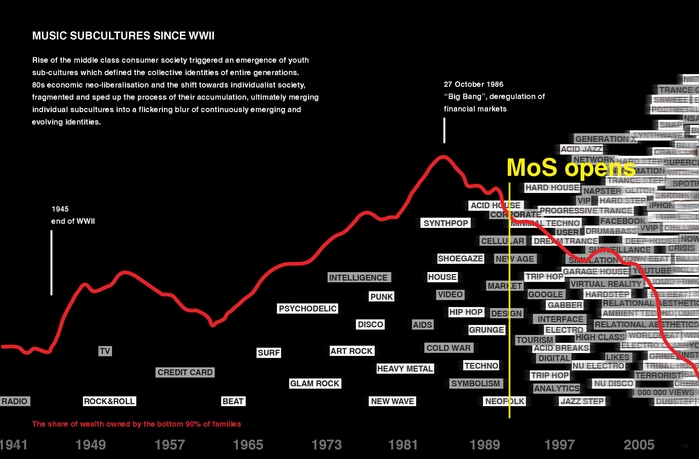

While researching this phenomenon I encountered papers on Harley-Davidson owners, punk music listeners, Dutch black metal fans, collectors of strategy games, and at least a dozen other subcultures. In each, an authenticity construct having to do with commerciality and consumption is shown to be important to identity. What is distinct about hipster culture is that it was primarily a culture of seeking, consuming, and performing authenticity. Thoughtful literature on hipsters is limited, but two recent theses (including Henke, quoted above) and Magill’s book on hipster identity support this finding. This means that change in the broader notion of authenticity in the West should therefore be highly visible in hipster subculture. Inversely, as hipster subculture changed, so would this broader notion of authenticity. This, in fact, is exactly what happened. The history of 21st century authenticity is the history of hipsters and their disappearance.

Authenticity as Aesthetic

According to popular wisdom, hipster culture peaked in the years following the 2008 financial crisis. The theory goes that economic uncertainty during the recession caused people to value history, heritage, and long-lasting goods. Moccasin boots, hand-drawn lettering, beards, artisan ketchup, and other ostensible signifiers of old-timey values exploded in popularity. Some have suggested that authenticity-seeking is nostalgic or charged with historicist fantasy (Wang, 1999). This may not be true at all times and places but it certainly was in Brooklyn ten years ago. Hipsters were the first to adopt the new outfit and these items began to replace the skinny jeans, crunchy headbands, and neck scarves of yesteryear.

The prolific indie music blogger known as Carles wasn’t the first to notice this shift (presciently immortalized in his blog title “Hipster Runoff”) but he understood it best. He saw the emerging aesthetic landscape of authenticity goods—reclaimed wood, Edison bulbs, chambray shirts, and so on—and dubbed it “Contemporary Conformism.” Carles was suspicious and resentful of this new hipsterdom, which he intuitively saw as diametrically opposed to the authenticity of his beloved indie music culture:

Auth music doesn’t really have a wide-reaching sound. It is not ‘scalable.’ Auth is not aimed to be a generically scalable trend/aesthetic to be implemented 4 the purpose of generating ‘youth culture dollars’….Auths do not have a visual aesthetic like ‘hipsters.’ Auth is a state of mind where you cannot be influenced. U can only vibe and approach the world with an auth state of mind. No brands represent u. Music is not cultural currency.

The key word from this selection is “scalable.” Carles recognized that aestheticizing authenticity would allow the popular, the generic, and the standardized to become authentic. This meant even commodities could be authentic—as long as the commodities signalled how authentic they were. You already know what the language of authenticity sounds like: “artisanship,” “craft,” “small-batch,” “single-lot,” and so on. Visually, authenticity signals are best demonstrated by New York City’s successful local chain The Meatball Shop, where antique meat grinders hang inside a faux-aged facade painted with mock-aged 1900s hand-lettered type.

These signals are effective because they evoke the character and logistics of historical non-commodity modes of production and slap them on modern ones. They suggest that the buyer is supporting a hardworking craftsman, laboring to make goods by hand. Needless to say, this mostly wasn’t true. Nevertheless, these authenticity commodities, from natural veg-tanned leather belts (brown leather was everywhere) to burr coffee grinders, could now be embraced and consumed without ironic distancing, representing a significant departure from the earlier hipster value system. “Authenticity” underwent a semantic expansion.

This transition from hipster-as-music-snob to hipster-as-conscious-consumer didn’t happen everywhere at once and the resultant confusion pretty much killed everyone’s agreed-upon definitions of what exactly a hipster was. In Olympia, WA I was still in high school burning “best indie songs of the year” CDs while college grads were lacing up their Red Wings in gentrified Williamsburg, commonly seen to be the center of the movement. But by 2012 it was finally possible to call just about everyone a hipster. The development of the authenticity aesthetic made it possible for the mainstream to participate in the most outwardly visible ritual of hipster behavior: authentic consumption.

Authenticity at Scale

It’s now 2018 and authenticity has scaled past the point of human intervention. It’s gotten to where even FMCG brands and fast food restaurants are calling their products “hand-crafted.” Carles sure as hell saw it coming.

Selections from the thumbprint motif at left on a McDonald’s in Hong Kong: “humanised, balanced, nourishing, ensemble, together”

Selections from the thumbprint motif at left on a McDonald’s in Hong Kong: “humanised, balanced, nourishing, ensemble, together”

Recently, Venkatesh Rao has put a name to the insipid version of this aesthetic visible in the commodity detritus left over from the rampage through major US cities as clueless brand strategists discovered authenticity five years too late: “premium mediocre.” The enthusiastic and notably global response to his essay suggests that awareness of exactly what has happened is finally dawning on mainstream culture.

At the same time “Brooklyn” has become America’s most significant cultural export. It’s not only 3rd and 4th-tier American cities that adopted the aesthetic. Among many other major international cities, the Shoreditch area of London developed its own version of Contemporary Conformism, as did Daikanyama in Tokyo (where the “Brooklyn” brand possesses cultural cachet as an update to the Americana aesthetic Japanese subcultures have fetishized for 70 years). Of course, America’s other main export during this time was Silicon Valley startup culture and the two found a perfect union and perfect distribution channel in AirBnB and WeWork.

It is impossible to think about the Brooklyn authenticity aesthetic, authenticity commodities, the “maker movement,” and startup culture as independent phenomena. It is not a coincidence that they all developed into mainstream culture at the same time. It might have been inevitable but the Great Recession certainly catalyzed the process.

High unemployment and unstable job conditions were the perfect circumstances for an accelerated entrepreneurship obsession. Financial conservatism and lower purchasing power aligned perfectly with the Etsy crafting boom and an emerging confluence of “makerspaces.” For those without maker skills, consumer connoisseurship of “craft” commodity categories like previous hipster mainstays coffee and denim became a popular choice of hobby and profession. This in turn contributed to the hundreds of restaurants and brands that all claimed to be part of the movement towards “local,” small production scales, heritage, and “traditional values.”

Venkat also makes the connection between economic anxiety and the authenticity aesthetic, going so far as to say millennial precarity “is the source of the [premium mediocre] grammar and visual aesthetic.” On the one hand this essay complicates Venkat’s model by adding the missing ethical dimension. As I have pointed out, the authenticity-based value system, subcultural identities, aesthetics, and the specific form of commodity capitalism involved are all interrelated. Venkat sees premium mediocrity as a “rational adaptive response” to being thrust into insecure economic circumstances, but we have already observed that the conditions for an authenticity aesthetic were developing long before the financial crisis triggered its eruption. On the other hand I’m reminded of Marx’s assertion that everything comes down to economics “in the last instance.” Maybe Venkat’s not wrong.

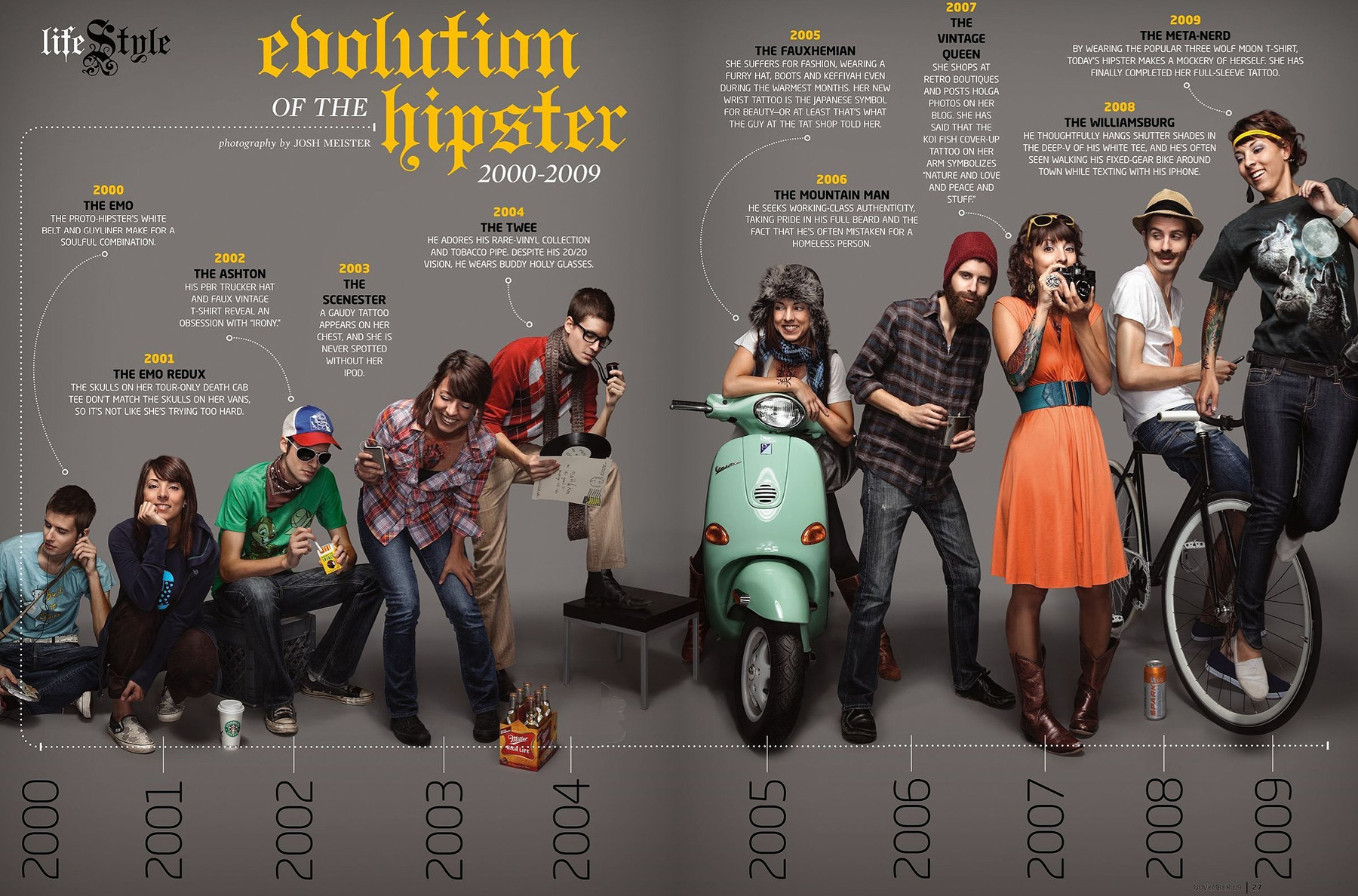

One thing is certain: the authenticity aesthetic served as a cohesive for all of these developments. It tied the spectrum of consumable items, spaces, and identities into a single unified visual experience. There could be no more perfect illustration of this entire series of events than Paste Magazine’s 2009 and 2015 satirical “Evolution of the Hipster” photo series. In the 2010-2015 session note the unironically worn authenticity goods (TOMS, Red Wings, leather dopp kit), the startup references, and the visibly inflating tech wealth of the demographic.

If your garage craft beer brand didn’t make it big, at least you could learn to code and join a startup. Unfortunately, when your new WeWork office displays the same hand-lettered signage as your neighborhood coffee shop, has the same brick walls as your fast casual farm-to-table lunch spot, and advocates the same “do what you love” message celebrity entrepreneurs have told you since grade school, it becomes impossible to think outside of authenticity politics.

Etsy office vs Brooklyn coffee shop Devocion

Etsy office vs Brooklyn coffee shop Devocion

Authenticity: a Personal Dimension

This is a good time to discuss the demand for authenticity and where it comes from. As I hinted at previously, there’s a personal dimension to authenticity. If you believe that a band or a brand can be authentic you probably believe in such a thing as an “authentic self” too. It turns out there’s longstanding historical precedence for this belief. The origin of the modern authenticity drive is the 19th century Romantic movement. The Romantics thought intensely-felt emotion was at the heart of beauty and therefore they valued the individual experience above all else. They rejected universal ethical frameworks and considered individual expression and the development of a unique self to be ethically valuable.

Although the Romantic belief system was later displaced by other movements in art and literature, it remained influential. It got a further lease on life when it was resurrected via 20th century existentialism, which proposed that individuals can only act “authentically” when they come up with their own values independent of other sheeple. These two value systems, romanticism and existentialism, have become encoded in modern cultural institutions. The cult of liberal individualism popularized by the “American dream” narrative, in which value is also premised on self-definition, is a classic example. The international art world spent the 20th century rewarding artists for establishing totally unique styles and movements rather than participating in larger “isms” like those popular in earlier historical periods.

Illustration courtesy of OMA

Illustration courtesy of OMA

The explosion of music and fashion subcultures is also well-documented. Hipsters were well-known to categorically deny the hipster label but when David Muggleton interviewed dozens of members of various UK subcultures in the 90s he found that most of them did the same thing. In many of his interviews “group identifications are resisted because they carry connotations of collective conformity, suggesting a concomitant loss of individuality that renders their members inauthentic” (Muggleton, 2000).

Clearly the cultural pressure to achieve a unique self is old, strong, and not unique to hipsters, so why did the authenticity drive spin out of control after CE 2000? One possible reason is that the hundreds of studies on authenticity in tourism and subcultures have also been read and in many cases sponsored by business thinkers who directly influence corporate strategy. Among brand strategists, millennials in particular are believed to be obsessed with authenticity; this assumption informs the creation of brand strategies which target those same millennials.

As millennials have grown to the largest group of consumers, brand guides and internal pitch decks have become littered with the A-word and its proxies. Joseph Pine and James Gilmore, the people who coined the influential concept “experience economy,” published another book in 2007 claiming the overarching strategic need of brands is to “render authenticity.” Whether or not this claim holds up today I will “render my opinion” later. Regardless, 2000’s hipster subculture and the subsequent rise of authenticity aesthetics has to be seen as the apotheosis of a prolonged historical need for unique selfhood that came to a frothy head in the early 21st century media-saturated environment of relentless brand marketing.

–

The thinking behind this essay was catalyzed when I tried to figure out the uncomfortable atmosphere of Dimes, a restaurant and deli close to where I live in Chinatown. After yet another awkward and vaguely hostile interaction with the deli cashier I vented on Twitter.

I do not understand the Dimes affect and I need someone to explain it to me

— Toby (@tobyshorin) June 27, 2017

A few tweets in I started to get somewhere:

Dimes people unironically take Kinfolk and Gentlewoman and Office Magazine as legitimate lifestyle suggestion

— Toby (@tobyshorin) June 27, 2017

These paper journals sit on a shelf at Dimes Deli for casual reading. Take a look at their websites. You’ll see lattes and spectacles arranged neatly on a table, you’ll see young artists collaborating with multinational fashion brands, you’ll see product editorials without any indication of their corporate sponsorship. It deeply bothered me that visitors and employees at Dimes seemed to have no problem uncritically accepting the lifestyles portrayed in these magazines, unironically engaging with the featured brands. I struggled and struggled to understand the mutual feeling of distrust between me and Dimes regulars, asking more questions until I finally exposed my own logic: didn’t they have a problem with how inauthentic it all was?

I can't figure out what Dimes people think is authentic, it's possible they are mutated post-authenticity millennials

— Toby (@tobyshorin) June 27, 2017

Venkat once told me that writing anything over 3000 words forces you to contend with your personal demons. I can confirm this to be true. This event kicked off a long period of reflection and embattlement with the fact that my own ethics—even my own sense of self—were based on authenticity. At the time, I was trying to change my unhealthy relationship to work. For years my anxieties around work had centered on far-flung future goals—a sort of personal teleology about what I was supposed to achieve and the type of person I was supposed to become. It struck me then that there is a deep entitlement to the idea of an authentic self.

No wonder millennials, the Authentic Generation, all seem to think they can be the next Steve Jobs. If you believe in a “true self” that can be discovered or achieved you’re not a far cry from believing in destiny. Worse still, you could start extrapolating all sorts of conclusions from an imaginary “truth” at your “center.” It does not escape my attention that exactly this kind of assumption is at work whenever someone asserts absolute speech rights based purely on the combination of unique identities they can lay claim to. The more differentiated the self, the more defensible this demand tends to be. Identitarianism is mirrored in—would not be possible without—the widespread preoccupation with authentic selves. In the future we may be able to look back at toxic wantrepreneurship, white entitlement, and identity politics both “left” and ethnonationalist as being underwritten by the same philosophical blunder.

After Authenticity

Meanwhile, years of semantic slippage had happened without me noticing. Suddenly the surging interest in fashion, the dad hats, the stupid pin companies, the lack of sellouts, it all made sense. Authenticity has expanded to the point that people don’t even believe in it anymore. And why should we? Our friends work at SSENSE, they work at Need Supply. They are starting dystopian lifestyle brands. Should we judge them for just getting by? A Generation-Z-focused trend report I read last year clumsily posed that “the concept of authenticity is increasingly deemed inauthentic.” It goes further than that. What we are witnessing is the disappearance of authenticity as a cultural need altogether.

Under authenticity, the value of a thing decreases as the number of people to whom it is meaningful increases. This is clearly no longer the case. Take memes for example. “Meme” circa 2005 meant lolcats, the Y U NO guy and grimy neckbeards on 4chan. Within 10 years “meme” transitioned from this one specific subculture to a generic medium in which collective participation is seen as amplifying rather than detracting from value.

In a strange turn of events, the mass media technologies built out during the heady authenticity days have had a huge part in facilitating this new mass media culture. The hashtag, like, upvote, and retweet are UX patterns that systematize endorsement and quantify shared value. The meme stock market jokers are more right than they know; memes are information commodities. But unlike indie music 10 years ago the value of a meme is based on its publicly shared recognition. From mix CDs to nationwide Spotify playlists. With information effortlessly transferable at zero marginal cost and social platforms that blast content to the top of everyone’s feed, it’s difficult to for an ethics based on scarcity to sustain itself.

K-HOLE and Box1824 captured the new landscape in their breakthrough 2014 report “Youth Mode.” They described an era of “mass indie” where the search for meaning is premised on differentiation and uniqueness, and proposed a solution in “Normcore.” Humorously, nearly everyone mistook Normcore for being about bland fashion choices rather than the greater cultural shift toward accepting shared meanings. It turns out that the aesthetics of authenticity-less culture are less about acting basic and more about playing up the genericness of the commodity as an aesthetic category. LOT2046’s delightfully industrial-supply-chain-default aesthetics are the most beautiful and powerful rendering of this. But almost everyone is capitalizing on the same basic trend, from Vetements and Virgil Abloh (enormous logos placed for visibility in Instagram photos are now the norm in fashion) to the horribly corporate Brandless. Even the names of boring basics companies like “Common Threads” and “Universal Standard” reflect the the popularity of genericness, writes Alanna Okunn at Racked. Put it this way: Supreme bricks can only sell in an era where it’s totally fine to like commodities.

Crucially, this doesn’t mean that people don’t continue to seek individuation. As I’ve argued elsewhere exclusivity is fundamental to any meaning-amplifying strategy. Nor is this to delegitimize some of the recognizable advancements popularized alongside the first wave of mass authenticity aesthetics. Farmer’s markets, the permaculture movement, and the trend of supporting local businesses are valuable cultural innovations and are here to stay.

Nevertheless, now that authenticity is obsolete it’s become difficult to remember why we were suspicious of brands and commodities to begin with. Maintaining criticality is a fundamental challenge in this new era of trust. Unfortunately, much of what we know about being critical is based on authenticity ethics. Carles blamed the Contemporary Conformist phenomenon on a culture industry hard-set on mining “youth culture dollars.” This very common yet extraordinarily reductive argument, which makes out commodity capitalism to be an all-powerful, intrinsically evil force, is typical of authenticity believers. It assumes a one-way influence of a brand’s actions on consumers, as do the field of semiotics and the hopeless, authenticity-craving philosophies of Baudrillard and Debord.

Yet now, as Dena Yago says, “you can like both Dimes and Doritos, sincerely and without irony.” If we no longer see brands and commodity capitalism as something to be resisted, we need more nuanced forms of critique that address how brands participate in society as creators and collaborators with real agency. Interest in working with brands, creating brands, and being brands is at an all-time high. Brands and commodities therefore need to be considered and critiqued on the basis of the specific cultural and economic contributions they make to society. People co-create their identities with brands just as they do with religions, communities, and other other systems of meaning. This constructivist view is incompatible with popular forms of postmodern critique but it also opens up new critical opportunities. We live in a time where brands are expected to not just reflect our values but act on them. Trust in business can no longer be based on visual signals of authenticity, only on proof of work.